A History of Storage: Database (DBMS)

A survey of database history and its various paradigms

As we continue this series, looking from a high level at the evolution of persistent storage technologies, we arrive now at the database. More precisely the database management system (DBMS).

Because of the wide array of systems that can fall under the DBMS, our focus here today is largely on the “paradigm shifts” in the field of DBMS technology. Again at a very high level, for those wanting to dip their toes in the water.

CODASYL: The Data Base Task Group

For those who have read with us before, the introduction of magnetic disks in the 1960s paved the way for many other revolutionary developments in storage technology.

As data stores scaled, so too did the need to access such data efficiently.

Traditional block storage access was characterized by physical disk addresses. Memory pointers. Relationships between data were identified by where they lived.

The management overhead around address management increasingly introduced difficulties that became a priority to remediate.

In 1959, the Conference on Data Systems Languages (CODASYL) has formed to address technical standardization and developing a common computer programming language.

The development of COBOL reignited the question of data processing and access standards.

As part of CODASYL, the Data Base Task Group was formed to invent a new model.

By I, Jbw, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15230892

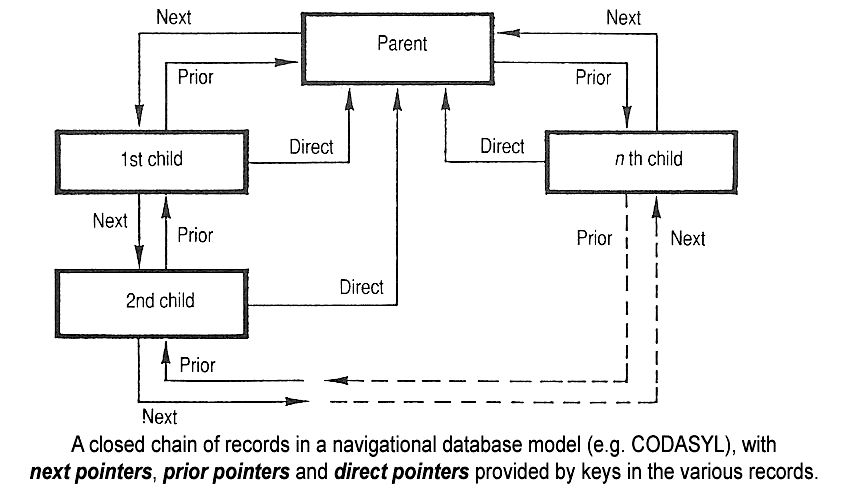

They came up with the Network Data Model.

The primary idea behind this data model was to replace the hierarchical tree-like structure of traditional data modeling with a more graph-like approach where parent and child records had a many-to-many relationship rather than a one-to-many.

This would offer low-level power for data access and processing.

However this model never took off in its own right for a variety of reasons. Foremost though was its rival we will consider next.

One item worthy of note here is that the CODASYL Network Model was the first to introduce the distinction between a DDL (Data Definition Language) and a DML (Data Manipulation Language) which is so common in the DBMS landscape today.

Origins of the Relational Database

The network approach was not the only proposed solution to data processing needs.

At IBM, in response to concerns about data scaling, a certain Edgar Codd authored a paper “A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks” in 1970 which proposed representing “collections of relationships” that could be accessed independently of memory addressing.

This concern with the user-friendliness of data access patterns is stated most succinctly here:

Users should not normally be burdened with remembering the domain ordering of any relation (for example, the ordering supplier, then part, then project, then quantity in the relation supply). Accordingly, we propose that users deal, not with relations which are domain-ordered, but with relationships which are their domain-unordered counterparts. To accomplish this, domains must be uniquely identifiable at least within any given relation, without using position. (Codd, 380)

Codd describes the previous model like this. If there was a data set on cars and their attributes, and if one wanted details on an individual car, they would need to perform address lookups to:

Use an address reference to find the particular Model in a section of addresses assigned to car models

Use an address reference to find the particular Make in a section of addresses assigned to makes of the various cars

Use an address reference to find the particular Color in a section of addresses assigned to the colors of various cars

Etc.

Instead the user should only be required to perform one lookup for the particular car which would then provide a collection of relationships including Model, Make, and Color, etc.

The practical advantages of this are self-evident. This is Data Modeling 101.

While Codd propounded “time-varying” relationships as the secret ingredient of relational modeling, the more significant proposal was the application of relation theory to computer storage access, i.e. storage access independent of memory addressing.

From here could emerge the concept of data tables with identifying links between them.

This offers a greater degree of logical abstraction and flexibility than the CODASYL Network Data Model could. Its favorability increased in conjunction to hardware and networking advances that offset the comparative advantages of “low-level” power the Network Data Model had offered.

Relational data would define the landscape for decades, even to this day.

The Introduction of SQL

Codd had introduced an idea, but ideas like a relational data model need to find a way into practical implementation.

How does one build this new relational database (RDBMS)? How do we get past an index-based addressing system?

IBM though slow at first on the uptake answered with Structured Query Language (SQL).

Standardized in 1986/1987, particularly with ISO/IEC 9075:1987, SQL attempted to accomplish several new things.

First, it provided an abstraction that allowed the user to access multiple records with one command without needing the address for those records.

Second, it went beyond the DDL and DML segmentation introduced by CODASYL and identified Data Query Language (DQL) and Data Control Language (DCL) as well.

Ironically while SQL made great strides in standardization and hardware interoperability, there remains considerable incompatibility between the particular flavors of SQL which themselves may or may not align completely with the SQL standard itself.

A few of the main household names we will go over now. More depth could be provided perhaps in a future post.

PostgreSQL was developed initially in the 1980s at Berkeley to replace the Ingres project that came before it (hence post-gres). Ironically it was not originally a SQL project and went through several name changes and functional changes over the years. In 1994, however it gained its first SQL interpreter and has standardized around it sense. It remains completely free and open source.

MySQL was developed by a Swedish company (MySQL AB) around the same time with a release in 1995. Based on the InnoDB storage engine, it would eventually be swallowed up by Oracle in 2010. While MySQL is open source it also does offer proprietary licenses. (MariaDB was an offshoot of MySQL before Oracle’s acquisition as well.)

In the last 1980s, Microsoft sought to establish their own proprietary implementation of SQL, launching SQL Server 1.x in 1989 targeting Microsoft’s enterprise customer base while offering editions for other kinds of users and business as well.

The NoSQL Umbrella

SQL was the rage of the 90s.

But as technology changes, so too do its needs.

It a testament to the robustness of the SQL and relational model that is remained so definitive and comprehensive for as long as it did.

In point of fact, needing to categorize very distinct database types such as graph and document under the NoSQL label shows the extent to which the SQL mindset dominated the field.

By the 2000s, database technologies are moving rapidly in divergent directions.

We will name a few of the alternative paradigms that emerged and have since become fairly established in the technology world.

Embedded (Key-Value)

The embedded database is built around tight coupling with application or hardware logic. It is simple, linear, with low latency.

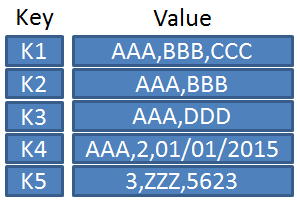

As its name indicate, the key-value table features one key mapped to a “value” which could include either a very boolean or complex, nested data. In this sense, it is semi-structured data.

Clescop, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

One common design pattern is a “Single Table” design which allows the user to forego multiple table lookups for more high performant queries, given the table’s data model is properly architected.

The embedded KV had existed in various forms even before the primary SQL vendors.

One could argue it was first standardized in its own right by Berkeley DB (BDB) which was released in 1994 as part of Berkeley’s own Unix derivative operating under BSD. While it is difficult to track down primary sources around its launch, here is a presentation of its logic from 1999.

BDB was acquired by Oracle in 2006, but its model paved the way for many competitors to develop their own ACID-compliant, high-powered DBMS systems.

Amazon DynamoDB was one such answer, announced by then CTO Werner Vogels in 2012.

Each of the major cloud providers has come up with their own proprietary implementation in the years since.

Document

The document database is a more nuanced approach to semi-structured data, further defining the key-value model.

The document database (not to be confused with a file server that stores document files) consists of a very particular sense of document.

This is tricky to define, because there are no generally accepted vendor-agnostic standards or protocols around this form of database.1 This ambiguity can turn this category more into a catch-all than one with hard-and-fast boundaries.

What is common across the major product families such as MongoDB, DocumentDB, CosmosDB, and Firestore are a few key dimensions:

A document is a standalone JSON-esque aggregation of data.

A document is the unit of both storage writes and storage retrieval with a unique address inside a larger set.

A document is schema flexible yet also indexable by fields.

Its primary strength lies in its fast iteration, particularly through hierarchical data. All the data attributes associated with an individual customer for example can be coalesced into a single document unit.

This provides for stronger horizontal scaling but also richer query power than traditional Key-Value offers.

However this does come at the expense of low performance for cross-document constraints and queries, but it works fairly well when a document can function as a self-contained microcosm.

To trace out its history, we can find antecedents in Lotus Notes (1989) and XML DBs like eXist-db (2000).

One Lotus Notes developer left IBM to create a self-funded instantiation of what is generally considered the modern document database: Apache CouchDB.

From here, the major vendors would kickstart their own versions, but CouchDB has seen widespread success and adoption, even as the backend for the npm registry, vulnerabilities notwithstanding.

Graph

While the network data model was set aside in favor of relational data in the 1980s, in the early 2010s graph data, would see a revival under the auspices of widespread social network adoption and the need to think in more network-based data persistence and access.

Neo4j paved the way for graph data technology by storing data elements as nodes, connected through edges.

Like DocumentDB there are no official standards around graph database technology, however efforts have been made to define these through Graph Query Language and the graph model which articulates the graph relationship through RDF (subject-predicate-object) language.

While Graph is not necessarily built to handle bulk OLAP workloads it does remain very powerful in terms of its first-class relationships, low-latency queries (at least when well architected), and allows for remarkably flexible schema evolution.

Vector

Vector databases are currently extremely hot with the genAI bubble dominating the market at the moment.

Vector data is unique in that it is not a formal protocol or query language but rather mathematically and algorithmically defined in how it handles the dimensionality of data.

So it is not possible to say that SQL and Vector databases are alternative options, as vector database implementations can live for example in Postgres with pgvector.

This goes back further than one would expect to the suggestion of Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) searches back in 1998. The basic idea of ANN is that it provides criteria for how “close to the mark” the query is rather than demanding total precision in what is returned.

This combined with mathematical representations of data as vectors where each dimension (of which there can be very many) is considered a feature of the data.

The tech giants each took their stab at this in the mid 2010s with Spotify’s Annoy for example or Facebook’s FAISS. But Hierarchical navigable small world (HNSW) would define the stage of these small graphs

There are of course other similarity search techniques, but HNSW is the basis for many vector data implementations across major vendors to this day, including Elasticsearch, MongoDB Atlas, and others.

This combined with the latest generation of LLMs has produced in large part the AI revolution that is currently underway.

Futures in DBMS

DBMS has come a long way since its introduction alongside the magnetic tape.

As data continues to grow horizontally, vertically, and in dimensionality, technology will of course innovate to meet the demands impressed upon it.

There are many different considerations to take into account here, but one interesting prospect is the advent of the AI Autonomous DB to further abstract the human from the loop of database development, consumption, and administration.

As with all things AI at the moment, we will see if we continue to approach the asymptotic curve as the major vendors fine-tune their models, or if another paradigm shift is in the cards to upset the playing field.

At least that I could find publicly available, please send to me if there are.