5 Considerations for Multi-Tenant Architectures

Designing multi-tenant environments for isolation and co-location

So you want to build yourself a multi-tenant ecosystem.

And you want to commit to it, all the way through production.

If you do, know that is a lift.

Today we will consider some of the most critical factors in the planning and evolution of multi-tenant architectures from my experience doing so for several companies at this point, and what I have learned along the way.

Terminology

First, a note on terminology.

Multi-tenant architecture can be terminologically confusing, particularly because assumptions are often built into these words, assumptions that are just as often not shared by everyone talking about it.

This can lead to confusion.

For example, if you are hosting an application with four hundred different commercial users, one could argue this is a multi-tenant application as each user is an independent “tenant” living inside the application.

This same person would then look at another application which consists of five near-identical deployments, with one customer group per deployment, and they would call this a single-tenant architecture.

On the flip side, someone could look at that application with four hundred users and say it is single-tenant, as there is one deployment that corresponds to the production environment.

They would then look at the five-deployments application and say it is multi-tenant, as the production environment has five tenants for the one environment.

The key distinction here is what “tenant” refers to. Both views are arguably valid but have very different understandings of what it is multi- with respect to.

We will define “tenant” as an infrastructurally-isolated instantiation of an application deployment for purposes of data or functional isolation.

This assumes that a “tenant” is a more granular subdivision of infrastructure beneath the “environment” layer (e.g. dev, qa, prod).

It also means that highly available (HA) environment architecture perhaps with an Active/Active or Active/Passive configuration would not necessarily introduce multi-tenancy, since the data or compute is not strictly bounded into one or the other.

Therefore a single-tenant deployment would mean one instantiation of an application in prod.

If there is one deployment per customer, that would entail a multi-tenant architecture. At least for our intents and purposes here.

1. Do You Really Need Multi-Tenancy?

This should be the architect’s go-to question when facing any net-new consideration: “Do you really need ______?”

If less truly is more, then is multi-tenancy really adding more than it will cost you?

This really does depend.

And it can be incredibly hard to forecast these variables if you have not lived through the growing pains of multi-tenant production ownership before.

Let us take into account some common reasons why companies push for multi-tenancy.

A. Data Isolation

Data isolation can be a very good reason for adoption a multi-tenant architecture, but it can also be an unnecessary one.

It can provide extremely secure safeguards to isolate the entire lifecycle of a single customer’s data if you instantiate separate tenants for each customer organization or BU you are working with.

But “data isolation” on its own is too broad and imprecise to be useful for a technologist in the way that it is for sales.

One must ask what types of data need to be isolated and to what extent and for what reasons?

The typical working assumption here is persisted application data such as in a PostgresDB.

But why is this necessary?

This requirement is most often driven by compliance or infosec teams, either internally or the customers’.

If it is compliance, then the question is which compliance frameworks are in scope for the application stack, or better yet, for individual application components.

If it falls under an information security program, then the question is which policies, standards, and baselines are in scope for the solution you are architecting.

Often enough, precisely mapping controls to components can lead to a relieving level of descoping.

It may be possible to achieve SOC 2 Type 2 certified compliance without needing multi-tenant PostgreSQL, if you can properly implement Postgres access controls and guardrails.

The minimum viable requirements for isolation may also shape the multi-tenant model you adopt. Perhaps separate Postgres databases are needed but can live in a shared cluster.

Multi-tenancy is not a one-size-fits-all approach as we shall see below.

Aside from the question of requirements scoping and mapping, another easy-to-miss possibility is whether the application stack itself already provides sufficient data isolation and guardrails, or is within a sprint’s distance of doing so.

This is a question of resourcing. For underresourced application teams it may simply be more viable to shift the load to infrastructure.

That is not a problem in itself, but it does come at a cost, a cost that runs with interest.

B. Noisy Neighbor

Some workloads are more intensive than others.

If customers are working inside a shared instance, particularly in an application without effective load testing or related protections, a power user may cause performance degradation for other users either through memory or CPU exhaustion, 3rd party API rate limiting, or exorbitant LLM token consumption.

Again the question may come down to (1) how well-designed or well-implemented the application itself is around handling load and putting in appropriate checks and balances or (2) what measures of vertical and horizontal scaling are in place to provide elasticity to support bursty compute requirements.

Sometimes that or a concerted refactoring effort may solve it.

Or if there is a special customer organization with heavy usage of the application, it may make the most sense across the board to provide them with a designated, isolated environment, so the blast radius of their system degradation is rather limited.

In this case it is more of a stopgap measure from a SRE perspective, but thinking beyond the pure technical architecture, it is a fairly effective customer relations move for those willing to pay or go along with it.

Where infosec teams are not involved, perhaps the power user wants the comfort of knowing they are using your SaaS offering in their own dedicated environment. Any slowdown is related to their heavy usage, not someone else’s.

An upsell to a premium isolated environment may boost ARR, particularly for larger customers, and this SKU approach is a valid business justification for supporting a multi-tenant architecture.

C. Easier Lifecycle Management

Perhaps there are not strict data isolation or performance considerations involved but for whatever reasons the application itself does not have robust data lifecycle management for users, groups, or workspaces.

If you happen to operate in a model with strict customer data deletion requirements and an application data model that really cannot service those needs, and no resourcing to implement such a procedure yourself, you may be backed into needing a multi-tenant solution here.

However this is overall a strategically weak reason for multi-tenancy if it is only one, and it behooves the technology strategy stakeholder to take a good, long look in the mirror and assess how committed they are to an application which cannot handle data lifecycle management well, and how long until that will be mitigated.

2. Choose Your Multi-Tenancy Model

If you do in fact decide to move forward with the multi-tenant architecture, the next question is the layer at which segmentation occurs.

This is a very broad spectrum and depends on the use case.

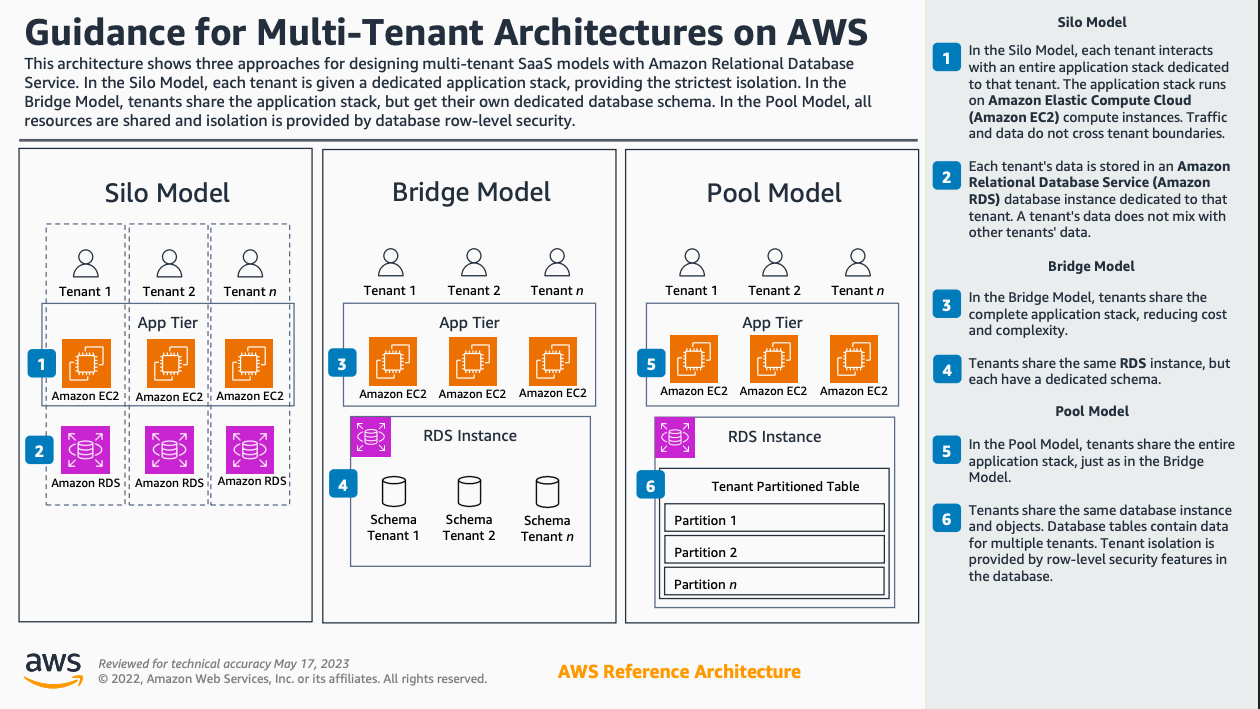

As the AWS example demonstrates above, you could theoretically have a multi-tenant architecture where the application tier is shared, but an individual RDS table is partitioned.

Or perhaps in the database tier it is the schema that is the partition layer, or the logical database, or the database instance.

In a silo model, you have dedicated application and database for each tenant, but this could be extended to the networking layer (VPC for each customer), or even beyond that to an AWS account per customer (leveraging Account Factory).

There are multiple dimensions to this, not just the single axis around the application stack itself.

If you have multi-tenancy, how do you then strategically group or partition:

Telemetry data

Audit logs

Big Data Analytics (OLAP)

SIEM/XDR and other security artifacts

Just to name a few.

This may or may not be complicated, again depending on the original requirements driving multi-tenancy in the first place.

But if for instance you require multi-tenancy for data isolation purposes, but your tracing or analytics tooling ends up piping sensitive data to a shared provider anyway, then you may need to think strategically about your analytics strategy.

The same goes if you have LLM models interface with sensitive data. If you depending upon embeddings, does your vector data store meet the criteria of data isolation? Or even with just inferential workloads, does your LLM observability tooling merely pipe all user prompts and context to a shared repository?

Anything that is tied to a driving component for multi-tenancy becomes a factor to consider.

This is part of the cognitive burden and potential complexity you must accept when moving forward with a multi-tenant architecture.

3. Change Management

Multi-tenancy introduces a fair degree of complication in the processes and procedures of change management.

Whereas in single-tenancy architectures change or patch management occurs once per environment (thus providing a very focused arena for change control), multi-tenancy often entails release management for each individual tenant

Let me provide just a few examples of where the complexity comes into play.

A. Fleet Deployments

The most obvious complicator is of course the deployment to each and every tenant in an environment for each release.

If you have N tenants in an environment, you will need to run the release playbook at least N times.

Automation is of course the compensating factor here.

But this really necessitates a robust CI/CD mechanism, one that can handle the nuances of multi-tenant change management.

GitOps pipelines are key here but again need to be robust for this to be a viable solution.

If you do not have the platform maturity to adopt full GitOps, then it is best to devise strategic patterns and guidelines for streamlining manual change operations as much as possible.

Bash and PowerShell can be a safety net in these situations, to account for gaps in your infrastructure-as-code or GitOps ecosystem, but they need to be handled astutely and with good judgment.

For instance, if the change request ticket includes a manual work item that is tied to a specific release, then there should be a concomitant effort by the ITSM, DevOps, or equivalent team to build out an automation of that manual work item which can then be run against the fleet during the release window.

Again, it’s a bit old-schooley, but the tradeoff of multi-tenancy is that most things change-management just become a heavier lift.

Whereas in smaller application ecosystems it may fully well be possible to have a polished GitHub flow and CI/CD pipeline that issues a new release for each approved commit, this may not be possible for multi-tenancy.

If you have a heavyweight, tightly coupled tenant architecture with a rolling restart deployment strategy, this would entail a lot of compute pressure to essentially reboot all the servers or containers tied to all tenants.

It is easy to identify solutions for this problem of course, but the fact that you do need a solution for it, does make it heavier than if you had single-tenant to begin with.

B. QA Strategy

QA and UAT rehash the same problems of manual versus automated testing.

With multi-tenancy, any number of manual QA tasks would need to be multiplied by N number of tenants. Unless you compromise your QA standards on this front and resort to strategic spot checking.

If you are able to invest in and achieve near 100% level of QA automation for a single environment, that is all well and good, but you may need to temper your expectations by recognizing just how feasible it is to run compute-intensive testing automations against an entire fleet of tenants, especially if you deploy a release more than once a day.

Furthermore, the engineering around such QA automation much also take into account multi-tenancy too, such as in how the headless QA tooling authenticates to each individual tenant, assuming there is not a shared admin user across the tenant environments (bad!).

Not unsolvable just more of a lift.

More than this, you have to account for the variability of QA results between different tenant environments.

What if QA testing succeeds in all but one tenant? What if it succeeds in 80 percent? 50 percent?

What are the criteria for a rollback? Do all environments get rolled back or just a few?Will the complexity of multiple live versions be accepted simply because of the urgency of the release or because the lift is not feasible?

Not all regressions are equal either, and if nearly all tenants are healthy but one or two have the equivalent of a Sev1/P1 release-introduced failure, there has to be tactical consideration on whether you rollback for all, for some, or try to fail the few forward and then patch the rest later.

C. Version Control

This of course leads into the aspects of version control which the multi-tenant stakeholder must account for as well, whether they like it nor not.

If we start off most simply with a monolithic single version for the entire tenant SaaS application stack, you have to identify your versioning strategy for the fleet.

Are there circumstances in which particular tenants may upgrade before others?

We noted just now the demands of the rollback strategy, but as is very common, various customers may have differing demands on their release cadence.

Some may prefer “move fast and break things” to opt in for new features while others may simply want their SaaS offering to work as expected all the time, regardless of bells and whistles.

This may lead to a business driven requirement for different release streams.

The advantage of multi-tenancy and leveraging Infrastructure-as-Code is that you can have very granular management of individual tenants’ versions without too much difficulty.

Sometimes it’s as simple as a Helm chart values.

But you have to account for the compatibility and version support of all deployed versions in the tenant fleet. If you need a critical security hotfix, you must be prepared to patch multiple different versions.

Additionally, if there is some feature flag tooling at play as well, this can quickly lead to a matrix of headaches around how to line up individual tenant versions with the suite of feature flags and their operational lifecycle.

Now take two dimensions of that matrix and add on the third dimension of microservice versioning.

If you have a microservices ecosystem, then each microservice ostensibly has its own versioning cycle and change management system.

If some microservices live within the multi-tenant offering while others live outside it but integrate directly with it, how do you orchestrate the versioning of shared versus tenant services for all tenants across all the versions for all the services currently supported?

This is another example of how multi-tenancy may not seem intimidating at first but can quickly become more than a thought problem as an organization or platform scales outward and upward.

D. New Workloads

On the note, of outward scaling, you can become fairly adept at accounting for multi-tenancy in your regular change management or release process, given you have a well-defined set of changes you are working with.

But an organization is not growing or thriving if it is not evolving. And the same goes for application architecture.

The development and integration of new workloads whether a Redis queue, a proxy server, a data warehouse, all need their rollout plans strategically aligned with the multi-tenant architecture.

To put it simply, it is simple enough to issue and mount a 3rd party API key for a single prod environment, but if requirements demand it, you may need to be able to programmatically generate and mount these for each individual tenant in scope.

What was relatively simple in single-tenancy becomes a thornier thing to solution for once you have N number of tenants to manage.

4. Other Operational Complexity

Outside the realm of change management, there are other additional considerations revolving around the ongoing operational complexity of managing multi-tenant workloads.

A. Snowflake State Management

The beauty of the customer is that they are not all the same.

Each have their own preferences and interests, and demands for custom-tailored solutions.

This is not inherently harmful but does pose a risk particularly when multi-tenant architecture becomes a vehicle for snowflake deployments.

Perhaps one customer wants a particular 3rd party integration disabled for security reasons, or another wants different caps set on file or data limits.

The beauty of multi-tenant architecture paired with infrastructure-as-code is that such granularity is in fact not only feasible but often easy to manage.

At least at first.

In a well-design multi-tenant platform, the actual implementation of snowflake state management can be a breeze.

But it comes at the cost of application coherence.

Product and engineering stakeholders may add feature on top of feature over time. More often than not these building blocks may have dependencies upon one another.

In a one-size-fits-all this is not as complicated to manage.

Yet if each tenant has their own bespoke configuration patterns, and the consistency of such configuration is not rigorously reviewed and maintained, it is only a matter of time before the snowballing of these snowflakes produces a reliability avalanche.

It is impossible for QA to catch these in pre-production environments unless you commit to some level of multi-tenant QA environment to account for the bespoke deployments of production tenants.

SRE stakeholders are fighting a losing battle of trying to corral in every possible permutation of config pattern that may cause regressions.

If any of this makes it way back to product and engineering, they themselves can express frustration because in their view they should not be required to account for each individual customer deployment’s requirements.

And so, without strategic coordinated effort, the multi-tenant bespoke deployments can devolve into a quagmire of both technical and personnel friction. High drag, low velocity.

While it is a well known adage that “config is cheap”, one must beware the force of compound interest. What once was cheap may quickly become taxing at scale.

B. Multiplied Incident Response

The same kind of operational complexity extends to incident response as well.

The classification of severity levels for incidents now has to factor in the probable occurrence where individual tenants may experience severe degradation but other tenants may have zero degradation.

How does this impact your SLI metrics? Do you take the same KPI hit for degradation in a few environments as you would for the whole tenant fleet? If these are accounted for differently, how do you properly distinguish between isolated downtime versus fleet-wide? What is the criterion for this threshold?

When an incident does occur in multi-tenancy, one must accurately assess and determine the scope of such an outage. One cannot merely say a particular degradation to the prod environment in most cases. Some tenants may be impacted while others are not.

Containment and remediation in turn follows this law of operational overhead. If the incident is tied to the tenant level, the lift to implement the fix in one tenant needs to be multiplied by the number of tenants.

In time-sensitive situations you are largely dependent upon the skills of your incident response team to create automated scripted remediations that can be run programmatically that will not negatively impact unaffected tenants, or introduce other regressions due to variation between tenants.

Institutional knowledge becomes a chief asset in these cases as those who know the ins-and-outs of your garden of multi-tenant peculiarities can often best assess the path of least resistance. Those with a documentation-based, or worse AI assistant-based, understanding of the application ecosystem may blindly step into the traps of bespoke deployments.

Often enough, a step or two of additional discovery is needed, and in general makes IR a bit heavier in both theory and practice.

5. The Cost

Out of all the above reasons, the multiplier factor of hosting multi-tenant environments should be the most acutely felt by the business line.

This is heavily dependent upon your application architecture, but if the silo consists of isolated web servers or databases or datastores or for some reason stateless API server can make all the difference in your hosting costs.

But in those cases where you do have to multiply a small chunk of CPU, memory, or storage per customer, this can very quickly be felt in the ultimate P&L statement.1

If you have slow customer acceptance this may be gradually accounted for.

But if you have fast customer acceptance, lowball the license fees to maximize market capture, and are committed to the multi-tenant architecture, the preparer for your financial statements may be surprised to learn that the cloud operating costs are a greater debit than the credit of customer revenue.

That is more of a worst case scenario in an early startup setting, but the same principle applies.

Many server-based solutions simply have that base level overhead to run N number of servers. Serverless and scale to zero may mitigate this to some level, at least for compute costs, but you may still have to reckon with any duplicated storage overhead for supporting individual tenant environments.

If you are a stakeholder trying to steer your organization away from adopting a multi-tenant architecture for a new solution, it may be through the rigorous arithmetic of computing cloud spend that you may be able to get buy-in to avoid or at least mitigate such an approach. If the other reasons fail to be persuasive.

Conclusion

While this may seem likely a largely negative assessment of multi-tenant architecture, this is not to say multi-tenant architecture is inherently “bad”.

There are many cases that justify the leap to this kind of approach.

It is just that many orgs who are bought into the multi-tenant approach for one reason or another may not fully know what they are getting themselves into.

And that is why these thoughts are merely presented here as a cautionary tale.

Multi-tenant environments introduce an additional layer of challenge.

These are not insurmountable.

But they increase that slope of uphill battle technologies teams are often engaged in, to fight the ongoing skirmishes of technology operations.

To build things that work. And stay working for the long haul. Hopefully without getting burnt out.

Not to mention this can often be masked for early startups by the generous credits their CSP may provide them with for initial vendor lock-in.